Early in the pandemic, ports closed, fishing fleets were grounded, and restaurants went on hiatus. Canned, frozen and direct seafood sales enjoyed a bump in demand. Reports of widespread changes were taking place across seafood supply chains. For the world’s 5th largest economy, California, the pandemic has caused an unprecedented disruption in seafood distribution. To understand changes in seafood consumption and supply, a group of researchers at University of California Santa Barbara and Santa Cruz surveyed consumers, marine aquaculture farmers and fishers throughout California beginning in July 2020. Here, we share preliminary findings that highlight how the COVID-19 pandemic created new challenges for seafood producers and changed seafood consumption patterns over the span of the pandemic. We end by identifying areas for increased research and support.

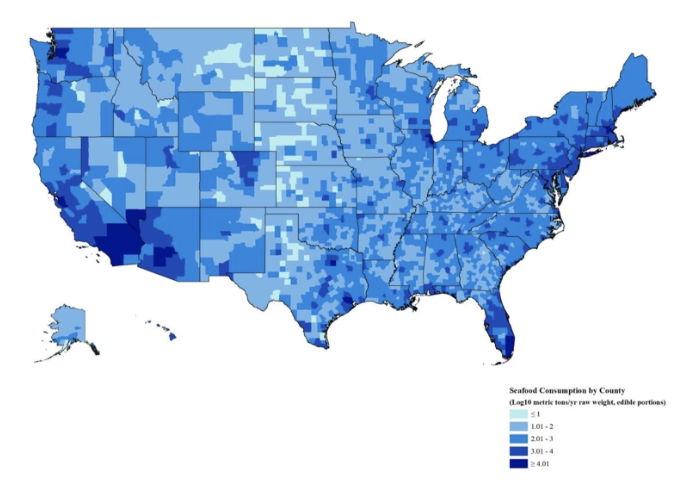

California has an outsized impact on food supply chains, both from the quantity and value of seafood produced and in its consumption. More people are employed in California’s seafood sector than in any other state (153,000 in 2017), producing 253 fisheries species and a few dozen farmed species. California consistently has some of the highest per capita seafood consumption in the United States.

Over the last decade, the diversity of seafood species consumed has narrowed in the U.S. However, with the growing popularity of direct seafood sales during the pandemic, this could shift, as could the substantial reliance on imported seafood. Over the last decade, Americans have been eating more of the same seafood species and more seafood at restaurants and food retail establishments. While the U.S. is a top seafood exporter, 62-65% of U.S. seafood is imported. Much of the imported seafood are commodity species –like shrimp and salmon – which can be more easily distributed, marketed, and sold through restaurants (31%) and grocery stores where the vast majority (56%) of seafood is purchased. Compounding the food service sector’s reliance on commodity species are the dietary preferences of U.S. consumers. When recently surveyed, North American seafood consumers reported purchasing seafood species in which they are already familiar.

In recent years, California has seen a proliferation of direct seafood networks, including Community Supported Fisheries (CSF), farmers markets, and farm stands. Local Catch Network, the largest site in the US for direct seafood sales reported 17 unique direct seafood sellers across California. Fishline, a direct seafood sales site, reported two additional markets in early November offering 22 species.

Seafood producers faced lower prices, now consumption is increasing

Our survey results show that during the COVID-19 pandemic marine aquaculture companies began shipping products directly to customers and offering delivery. Seafood cooperatives were also formed during the pandemic, some as informal associations of fishers and others joining to supply fisheries and aquaculture products directly to consumers. Despite these efforts, farmers reported selling much less. In addition, a third of farmers reported higher supply costs. As a result of pandemic related stressors, a large majority of farmers purchased and planted less seed, and harvested less.

Among fishers, some that traditionally sold to restaurants pivoted to direct sales, while those dependent on export markets worked to develop additional overseas customers. Most fishers surveyed reported a lower price-point than in previous years due to both the COVID-19 pandemic and the trade wars with China. Most felt they were not selling to their ideal customer and more than a third reported expending more effort towards marketing and selling.

When surveying seafood consumers between July 2020 and February 2021, we found that overall seafood consumption increased and avoidance of food due to covid concerns decreased substantially. Seafood consumption in restaurants may be rebounding and local CSFs have reported a bump in direct sales, but, less than 4% of people reported sourcing from places other than grocery stores or restaurants in the last month.

Forward Thinking

Fishers and marine aquaculture farmers faced compounding threats, from reduced prices due to the trade war to lost sales in the pandemic. For producers who shifted from restaurant sales to direct sales, significantly more work was required to sell a smaller volume of seafood. Here, state and federal support could help California seafood producers, through fisheries and aquaculture specific programs. Given their importance to coastal economies and communities, resources should be set aside to help fishers and farmers organize and market their product.

Our preliminary findings suggest that alternative seafood networks and direct sales are growing in importance in California, though the study only covers a small portion of direct sales. We suggest targeted research on California’s alternative seafood networks. Increased research efforts are necessary to support this emerging facet of the industry, both to understand the effect these points of sale have on seafood distribution and to ensure the policy structures are in place to support long term growth.

Seafood consumption in California took a dip in the first few months of the pandemic. While seafood consumption appears to be inching up, Americans have typically eaten less than the recommended amount of seafood. The reasons for this are complex. Culturally, most Americans are not as accustomed to cooking and eating seafood as other animal proteins, like beef and chicken. Outreach strategies are necessary to improve consumer confidence in buying and preparing a variety of nutritious seafood. Specific to local seafood supply chains, it will be important to understand the barriers and opportunities for producers and consumers in local markets, including cost/price, access to markets and product, access to processing infrastructure, and seafood handling training. There are also missed opportunities at several points of sale that could integrate more seafood into their offerings, including: hospitals, schools, food banks and prisons. Less than 0.5% of reported seafood consumption came from these sources despite their significant contribution to the American diet. Additionally, with the growing importance of food service sales for U.S. seafood consumption, a more-thorough investigation of the California seafood-restaurant market supply chain is warranted. This will help anticipate and adapt to shifting seafood demand.

This study ultimately aims to describe changes in California’s seafood consumption due to shelter-in-place orders, with special focus on the diversity of species consumed.

Recent Comments